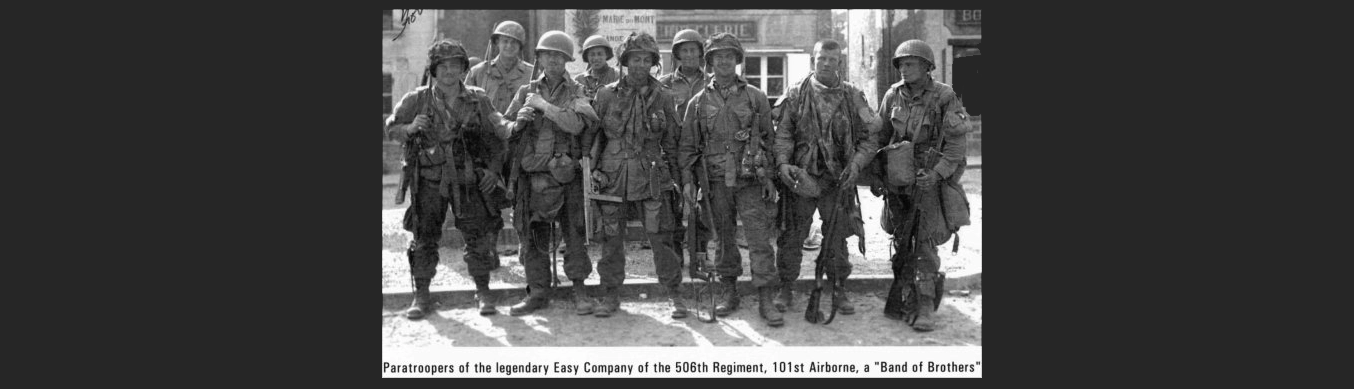

Today we have the pleasure of a double feature with celebrated Hollywood writer Erik Bork, one of the writers for HBO’s Band of Brothers!

First our context setting blog…followed by related questions to Erik.

By Luke Hughes (project lead)

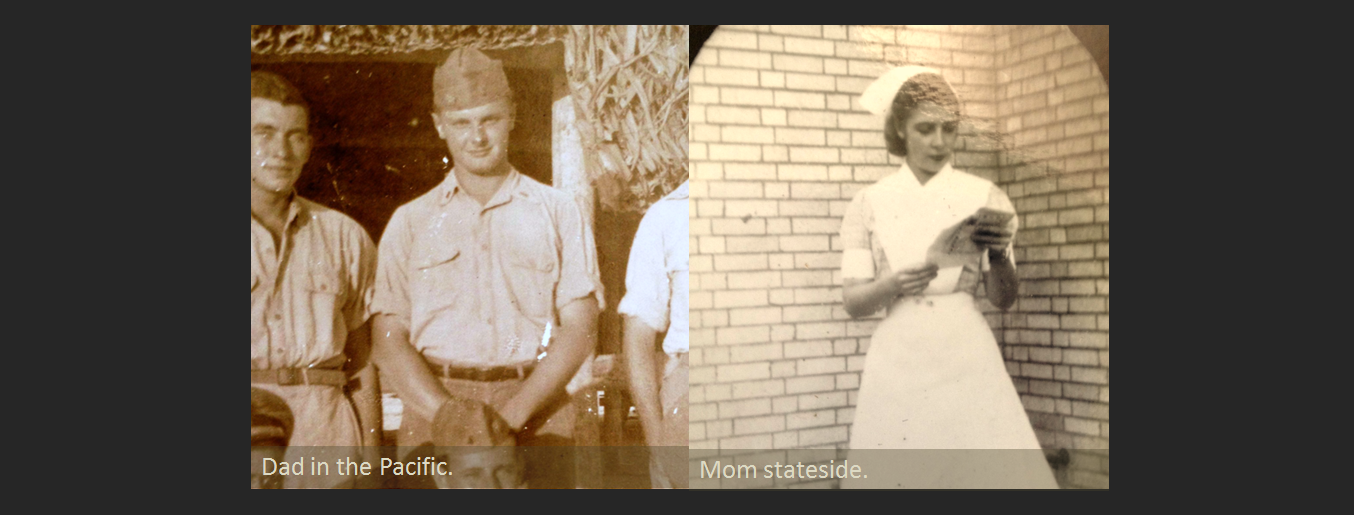

For me, history is personal

My father served in WWII. My mother as well.

My father was also an eminent historian, the founder of a historical field and a Pulitzer Prize Finalist.

For me history has never been an abstraction but the personal experience of my parents, just as it’s the personal experience of many of your parents and grandparents. Sometimes, lying in bed at night, as I thought of turning those experiences and often deaths into a game, I also wondered whether my late parents, my personal heroes, would be ashamed. It was under that early sense of burden that I came up with a simple design principle: Respect.

Respect: the easy part

When I brought Allen and Paul on as writers, and Mariusz Kozik on as portrait artist, I emphasized that our core tone must be one of respect, respect for the lives and experiences of those involved, for the dark side of their experiences, but also the light side of their sacrifices and commitment. Concretely, we adopted both HBO’s TV series Band of Brothers as a guide to that tone…

…as well as Vietnam Vet Karl Marlantes spiritually minded book:

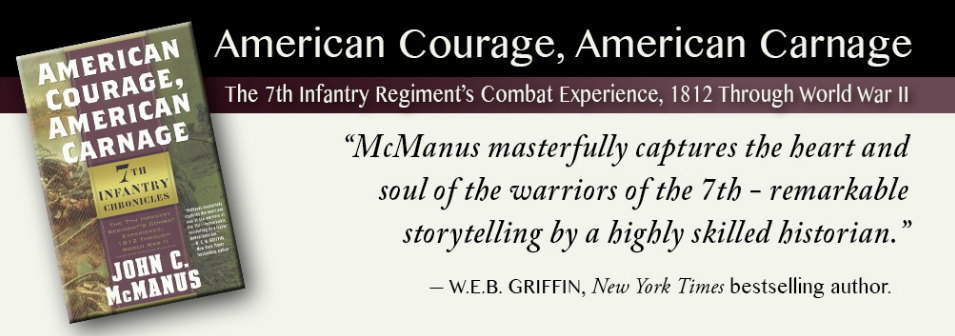

Further, in the spirit of that respect, we determined that we would follow a real unit, the fabled Cottonbalers, using as our guide eminent military historian John McManus’ wonderfully detailed book:

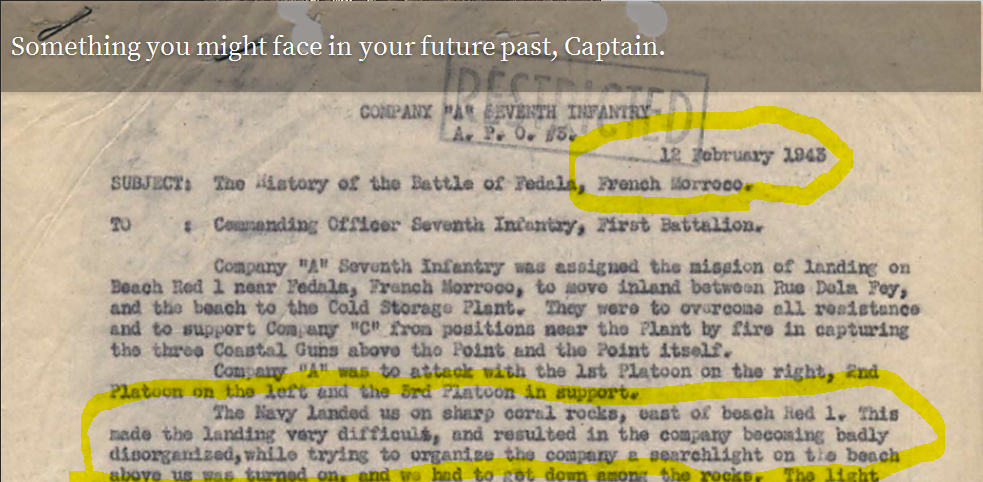

To our great delight, John agreed to advise us. We went so far as to hire an archivist to pull out first person reports of junior officers from the US National Archives:

Unfortunately, this pleasant, seemingly simple, decision to be respectful and therefore to follow a real unit, were where the problems began.

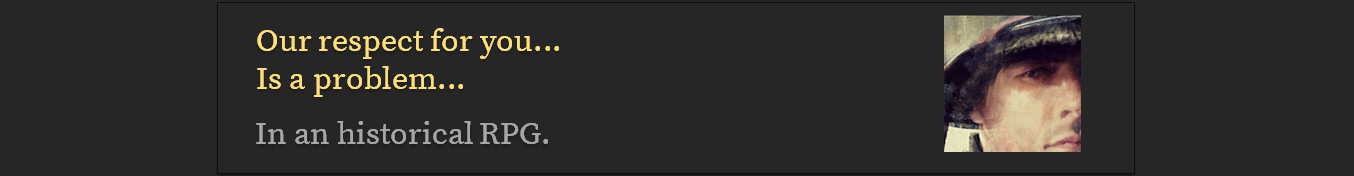

Our Respect for You…is a Problem!

Our first thought was to also follow specific real individuals, in the vein of Band of Brothers. However, by 2017 most of the actual participants were deceased or incapacitated. Second, we knew we wanted to do an interactive game where your decisions mattered. This meant that you could make your own choices and follow your own leadership journey. Yet, we wanted those decisions to be based on actual historic decisions. We abruptly realized we couldn’t do both: if we gave the player the ability to make decisions that diverged from history, we could hardly present an exact retelling of what actually happened. Burden of Command was not a movie.

Nickel Company

Our solution was to create a fictional company: Nickel Company. Your player character and the NPCs would be fictional, but would exist within the very real 3rd Battalion of the 7th Infantry Regiment. This allowed the interactive fiction writers and scenario designers the freedom to craft a compelling interactive narrative and allow the player the freedom to chart their own path while still embedding the player in the experiences of a historical unit and its real leaders.

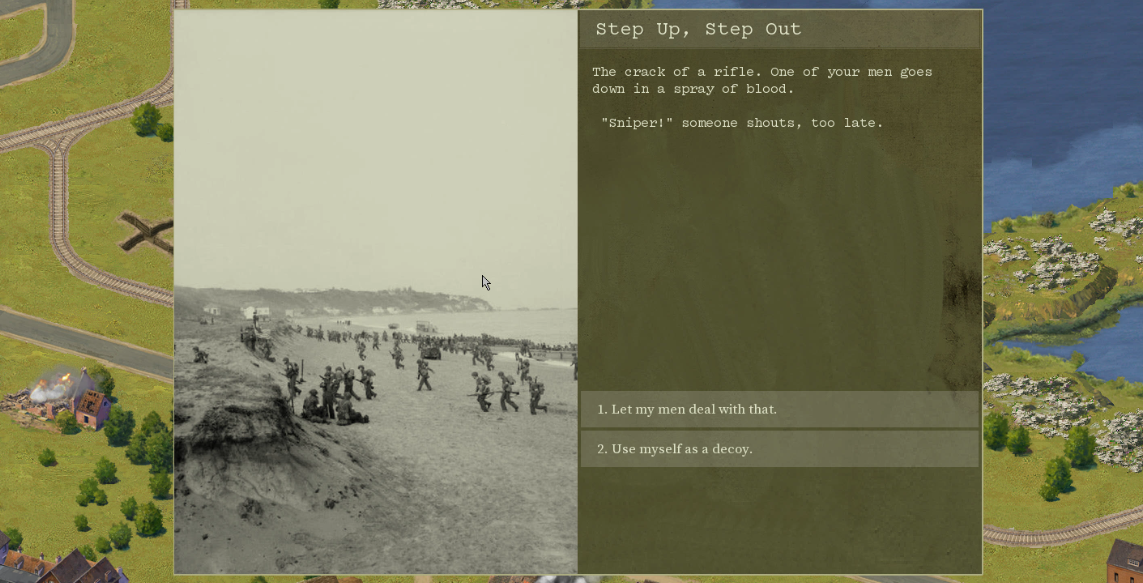

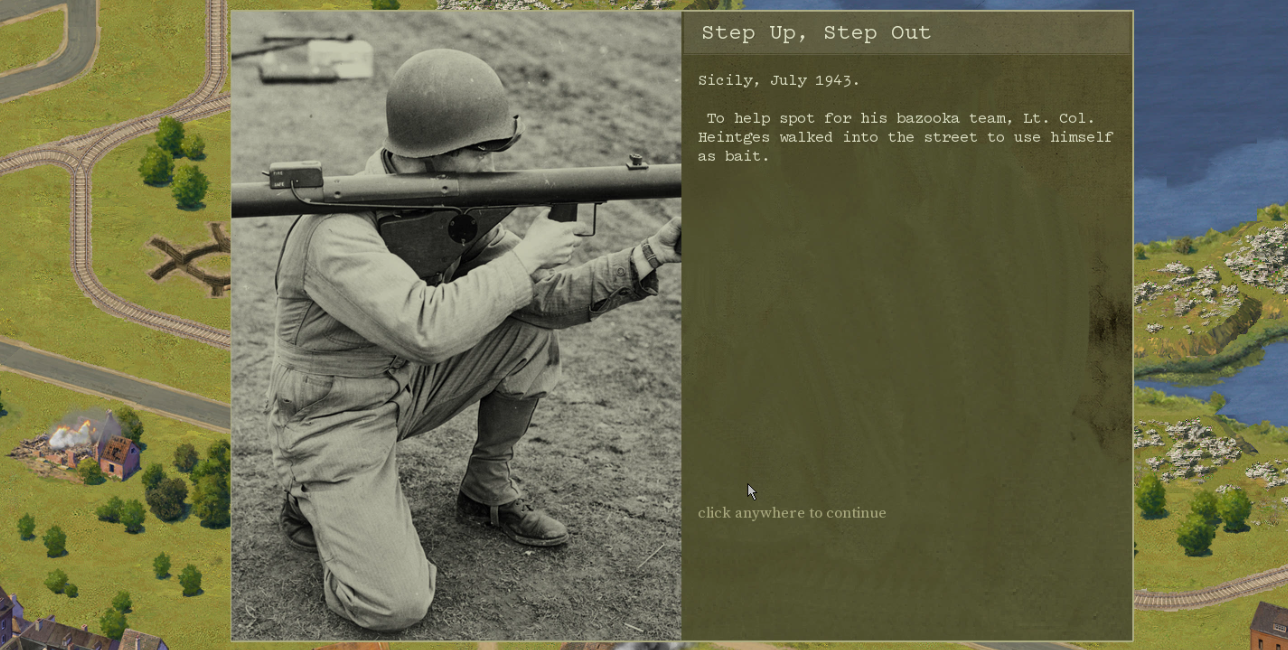

(and, FYI, here’s what the real leader decided to do):

The end result would be a historically immersive but personal leadership journey. See this dev blog for more on your RPG crafted journey:

The decision to use a fictional company not only gives us to cherry pick the most interesting events and decisions across three years of war but also the most engaging battles. In this sense, Nickel Company’s war is a lot like a ‘highlight reel’ of the Cottonbalers’ involvement in WW2.

Bend, but do not Break

Of course, giving ourselves the liberty to explore different decisions both narratively and tactically shouldn’t let us take too much license. To maintain our respect for what really happened, we developed a design principle: “bend, but do not break, history.” For example, we would not allow you to pull in “cool” units or leaders as reinforcements if they were not in range of the actual battle (Allen couldn’t use the Rangers early on in Sicily) but we would allow support that was close enough to plausibly intervene. Similarly, we would allow historic individuals to appear (typically superior officers) but in respect for their own journeys they would not change their own decisions or actions. While many RPG and historical games let you “save the world” or deeply change history (kill the ultimate baddie, reverse the outcome of a famous battle, etc.), we believe that the real experience of being normal civilians drawn into events much larger than themselves would be far more compelling. Here the success of Band of Brothers (a story of brave and admirable men, but one told on a very small scale) reassured us.

Process: The Wisdom of Crowds

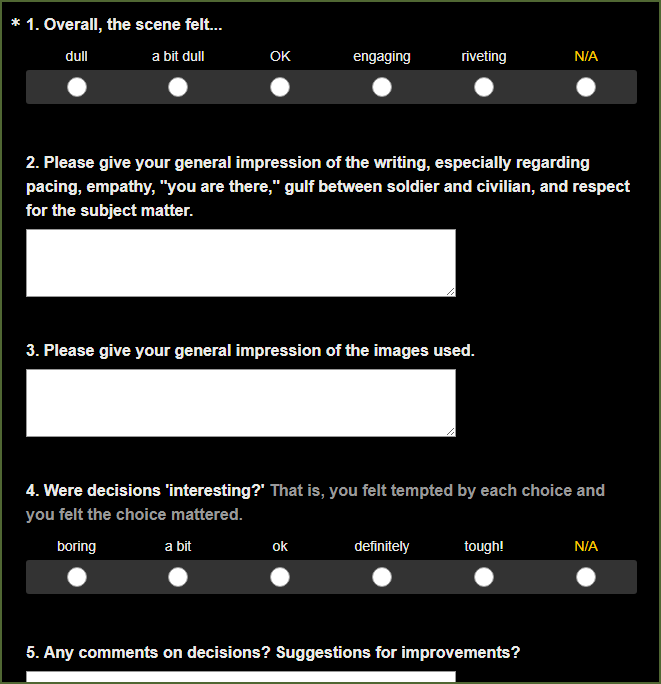

Principles are nice but I have always felt empirical feedback is even better. That is why we involve a remarkable set of advisors on both the narrative and game design side as part of our respect for your game experience. This illustrious crew includes Chris Avellone, Alexis Kennedy, Ian Thomas, William Bernhardt as well as many historical and military experts, including John McManus and a variety of military veterans (see Our Team). This is part of our respect for the historical individuals and their experiences. In addition, we’ve had the privilege of inviting gamers of very different stripes to give their own vital feedback. Lastly we established an ongoing process of surveys for each and every scene to give both qualitative and quantitative feedback. (This was incredibly useful- note by Allen)

This process has allowed us to assess how engaging the gameplay is while ensuring respect for history and the experience of military leadership.

Problem: the Bloody Decisions of Real Leaders

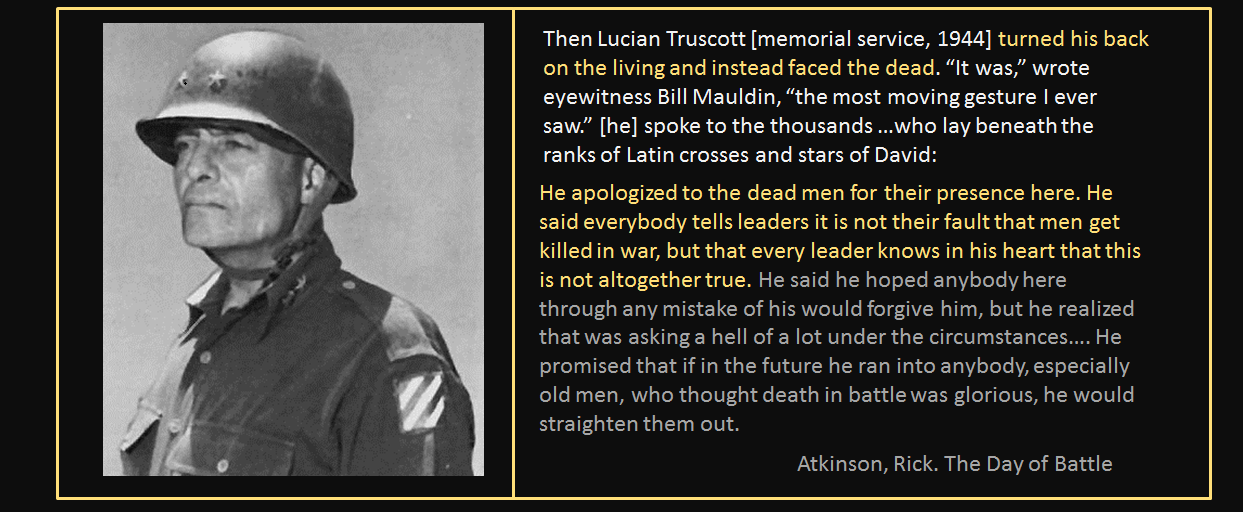

Our problems weren’t done. One of our early internal team arguments was what to do with historic decisions that in hindsight seemed to have cost unnecessary lives. On the one hand a respect for the truth of history suggested that, like a real historian, we show questionable decisions in an unvarnished way. On the other hand, a core respect for those who put their lives on the line made us hesitate to second guess the men who ordered and the men who died. We are not acting as historians, but as storytellers. Was it fair to call out in isolation the one bloody decision of an individual? Would that narrative tightness exclude other good decisions? Did we really know the full context of why they gave those orders that day? In brief, who were we to pass judgement? Our solution was to respect the individual in this case, and show humility as game designers. We would not directly call out bad decision of these actual individuals who put their lives on their line. Instead of rendering judgement, we would instead create fictionalized analogs of their decisions and put the player in those same boots. The hope is to teach us all a little humility for their historic burden of command. Below a quote from the fine commander of the Cottonbalers’s 3rd Division:

Problem: The Burden of Command

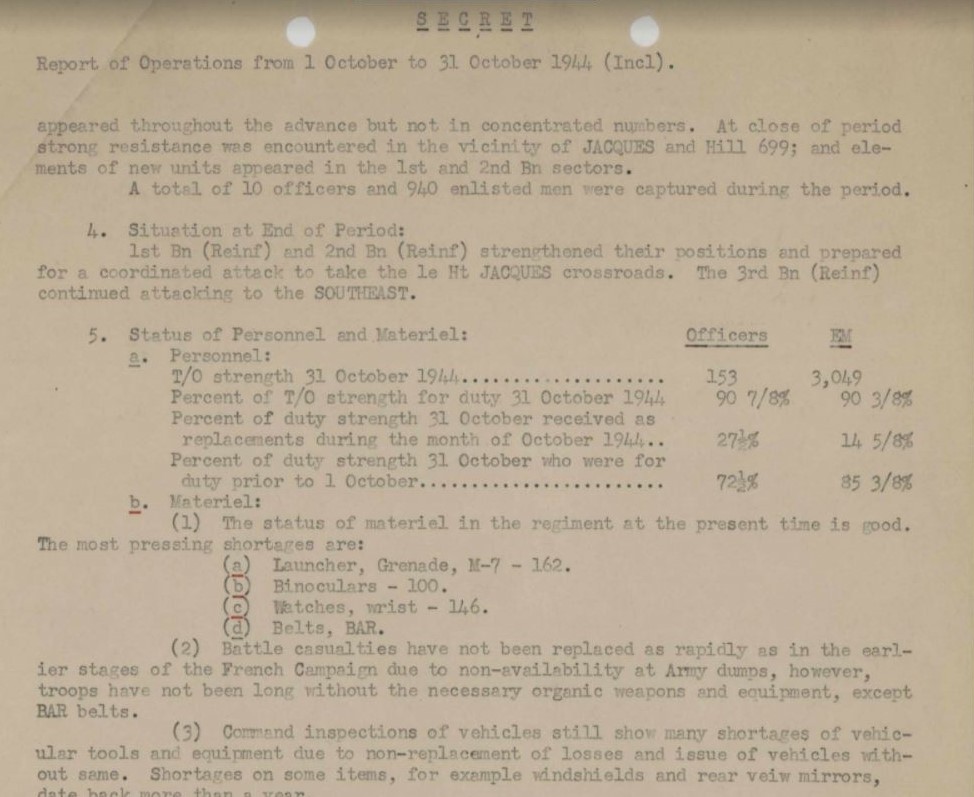

It is sometimes said that warfare is “months of boredom punctuated by moments of extreme terror.” A respectful pacing of the “boots of command” would have subjected you to a hundred administrative or logistical decisions for every taste of combat! On the other hand, dropping them would convey a false “hollywood movie” sense of leadership. Our solution was to actually give you an actual paperwork scene and make it interesting. After all if Papers Please could, why not us? As it turns out, this included several logistical dilemmas. Moreover, we had to make these moments into interesting choices as well. The good news is that I can tell you personally that one of the more stressful decisions in the game for me (darn you Paul) revolved around obtaining cans of scarce gasoline. And furthermore, that after sometime in the boots of an infantry Captain I actually found myself quite interested in where our supplies were coming from. Indeed, I felt a disturbing level of interest in seeing in the interactive fiction imagery of the historical reports that real officers worried over:

The Spiritual Reward of Success

Speaking personally again, and thinking of my departed parents as well the historical Cottonbalers, I can tell you now that when I stare at historical pictures of their experience I feel a deep connect across the decades. I believe this is because of the respect the team has striven so hard to distill into an emotionally authentic game experience. There is respect for those who served so that we may walk, at least a little, in their boots.

That feeling of connection across time, is powerful, moving, and a solace when I think of my parents.

Before plunging in, Erik wants to be clear that his comments do not represent HBO, production, Hanks/Spielberg etc in any capacity. Nor is this an endorsement from Band of Brothers. It’s just one person who worked on it recalling some thoughts on the experience.

1. Did you feel a tension between being true to the historical record in Band of Brothers versus telling a good story? Any examples our readers could relate to from the show?

Yes, I think this happens with any true story adaptation. One of the challenges with BOB is that the book was filled with anecdotes about events that happened to a very wide variety of individual characters, far too many for an audience to keep straight in the miniseries. We had to pick and choose who to focus on, in some cases giving smaller historical anecdotes to different characters or groups of characters, and omitting others (and omitting some characters). Some feel there are still “too many characters to keep straight and be invested in” in the miniseries, even after that, and I can’t say I totally disagree. It was something we struggled with.

Beyond that one example, there are many other things that we as writers/producers/directors chose to focus on, streamline, consolidate, adjust and fictionalize so that it would hopefully be coherent and compelling to an audience throughout. Real life just doesn’t give us what we expect from stories. There’s a lot of editing and re-imagining that tends to need to happen. But at the same time you want to stay true to the spirit of what really happened, and not change anything really important.

2. Did you have any debates around that with the real soldiers? That is they wanted a more literal telling while you wanted a more “emotionally true to the narrative” one?

I think there were times when they read or saw things and said they remembered them differently and we would sometimes adjust accordingly. Sometimes their memories disagreed with each other, since it had all happened 50 years prior. For the most part, though, they didn’t get too involved in overseeing what we were doing or giving feedback after the fact — though they gave us a lot of information (directly and through the original book) prior to and during the writing.

3. Did you have any narrative design principles that guided you in coping with any such tensions? For example, we adopted the design principle “bend but do not break history.” That is bend for a good game, but don’t violate the spirit of what really happened (or could have happened).

Similar to yours: be true in spirit and in as much detail as possible. Make changes only when absolutely necessary to make the story work better for an audience, and only in such a way that it won’t distort or fundamentally change what really happened.

4. Any hesitation in relating “bad decisions” made by real leaders in the war?

I don’t think we really had any of those other than the ones you see on screen, which seemed important for story purposes, and so no, no hesitation on those, as long as we knew from multiple sources that they really did happen that way.

5. Sometimes we have found that history is stranger than fiction. That history almost seemed too “Hollywood!” in fact we had to put in little history notes like “no this really happened in 1943 at….” Did you have a similar feeling? Examples?

I have definitely seen that happen. I can’t think of specific examples in BOB but if you asked me about something that seemed too “Hollywood” to a viewer, I might remember…

6. Did you feel an emotional connect across the years from telling such a real story or talking to the real men about their lives? (we are envious of that)?

Absolutely, that becomes a part of working on something so important/meaningful so deeply and for so long, including meeting the actual veterans and wanting to do right by them. Not only the writers and producers felt this, but also many of the actors who got to know the men they were playing.

| Follow @BurdenOfCommand |