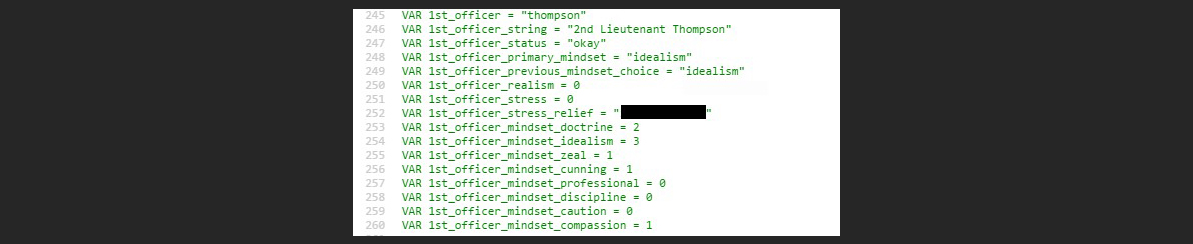

This is VAR 1st_officer, one of the components of your company in Burden of Command. Any squad that-

I’m sorry. Let me start again.

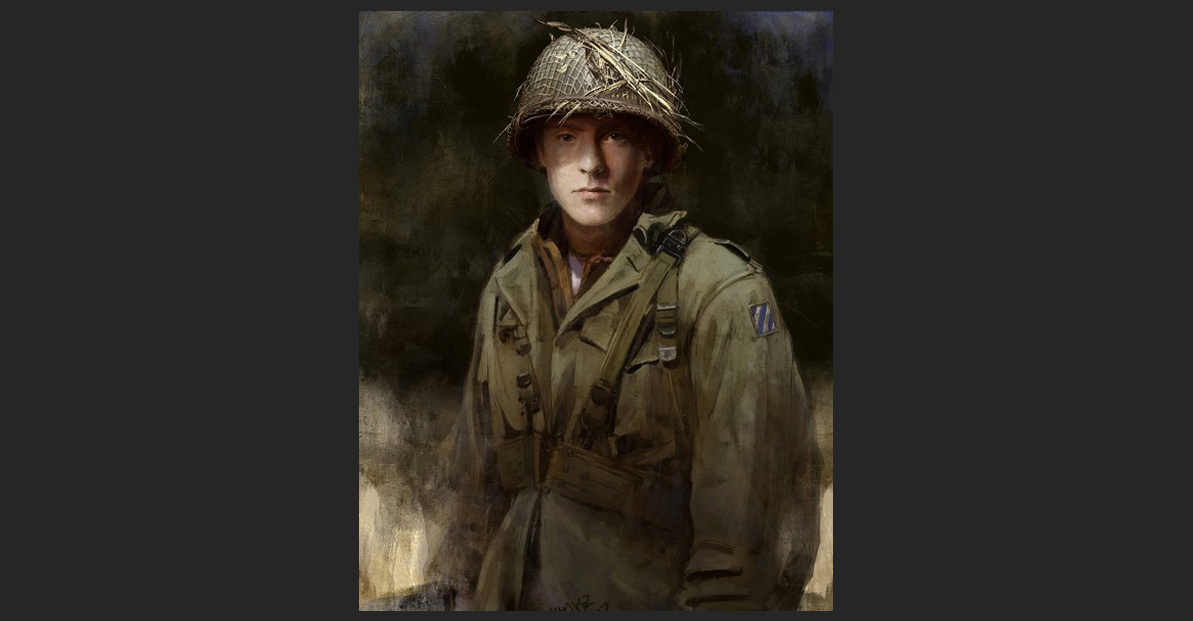

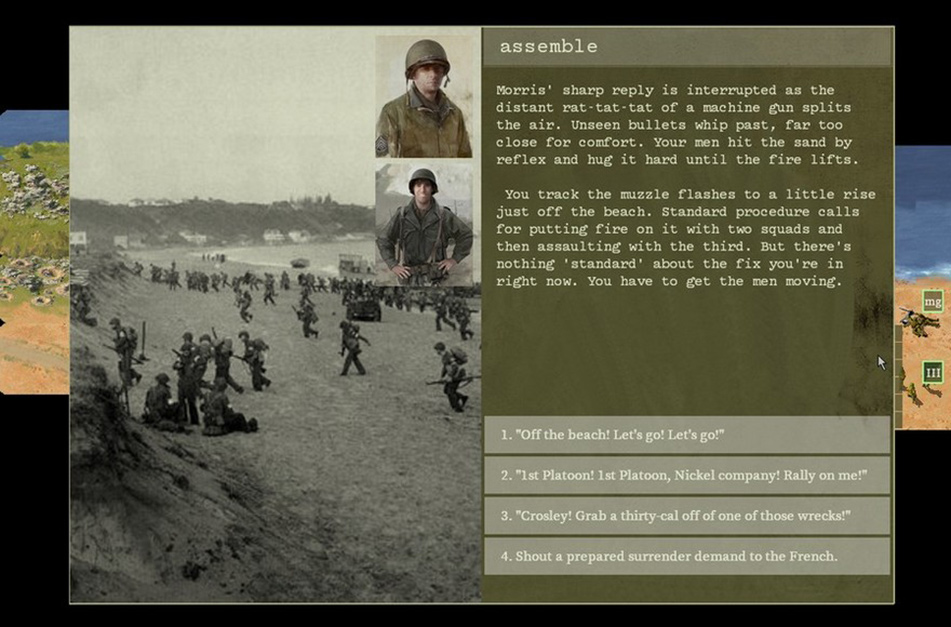

This is Edgar Gaines Thompson, the son of two schoolteachers from the small town of Piedmont, South Dakota. He was set to follow his parents’ footsteps when Pearl Harbor was attacked and the United States entered World War Two. Imbued by his parents with a strong sense of morality, he saw it as his patriotic duty to volunteer. A quick learner and a hard worker, he was quickly picked out as officer material. Still eager and bright-eyed, he takes command of 1st Platoon. His optimism and courage quickly makes him popular among his men, though some of your veterans shake their heads. They know that idealism rarely survives a trial by fire.

Perhaps he will return home to Piedmont with his idealism intact.

Perhaps he will end the war as an embittered man, old before his time.

Or perhaps he will end his young life on some nameless hill in Sicily, or Alsace, or Bavaria, his chest ripped open by shrapnel or his temple marred by a bullet wound, his hopes and dreams spilling out onto a soon-to-be forgotten stretch of soil far from home.

My name is Paul Wang, junior writer on Burden of Command, and I’m here to talk about building empathy.

When you play chess, do you care about your pawns? Do you agonize over sacrificing them? Or do you see them just as means to an end?

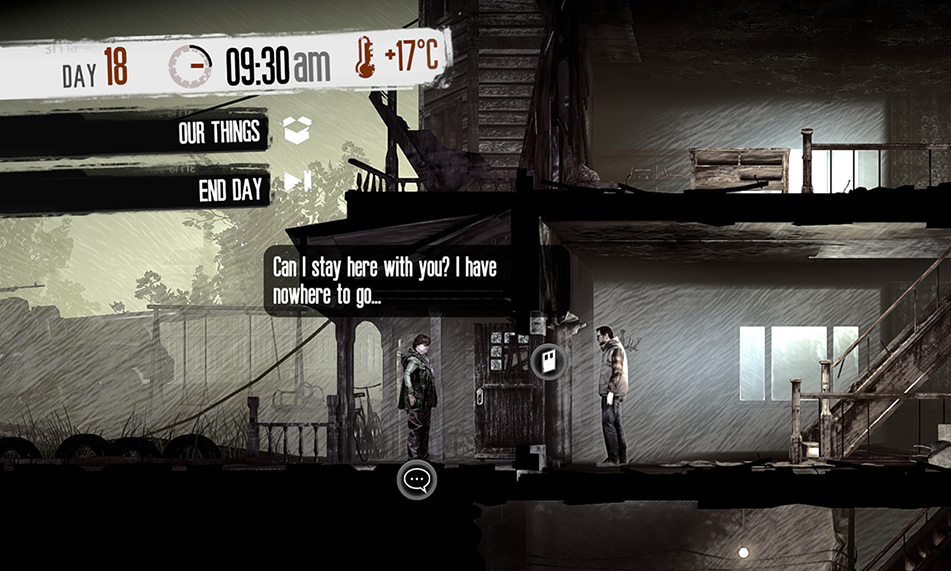

In 11Bit Studios’ This War of Mine, you also have pieces – a group of refugees – and a board – the fictional war-torn city of Pogoren. However, because of the way that the game builds empathy between the player and the characters they control, the player can’t sacrifice their “pieces” to win like they would in a game of chess. The question of how to achieve the win state (surviving until the end of the siege) becomes more complex because the player begins to identify with the characters, thinking not only of their own victory, but the well-being of these beleaguered, relatable, but ultimately fictional souls.

The player might find themselves weighing the emotional cost of forcing a character to visit suffering on others for the sake of obtaining much needed medicine or putting their characters at risk to “be a hero”. The nature of the win state itself changes. Is winning a matter of pure survival? Or is it better that they make it out with clean consciences that will let them live with themselves afterward?

The player begins thinking less like someone playing a game, and more like those who are trapped in a ruined building in a city filled with chaos.

Burden of Command is This War of Mine seen from the other side. Building bonds of empathy towards the characters under the player’s command serves to turn them into more than little olive drab men on a map. In return, as the player starts to empathise with their company, they begin to feel responsible for their well-being. They begin thinking of the win state not only as a matter of taking the objective, but as a matter of bringing as many of their boys home as possible.

They begin thinking like a Company Commander.

The question for a writer then becomes which characters to focus on building empathy with. Generally speaking, the average player can maintain empathic bonds with anywhere from half a dozen to a dozen characters. Anything more and things get dicey — after all, these characters have to compete for attention with a player’s real family members, friends, loved ones, and co-workers. Anything beyond those dozen characters, and players will start forgetting names, faces, and uttering the eight words no writer wants to hear: “I don’t care what happens to these people”.

A US army rifle company in 1944 had a total paper strength of 193. Realistically, we couldn’t make every single one of them into an empathetic character – players would lose track. We had to decide who we would build our core relationships around.

The four platoon leaders in the player’s company are the conduit to the nearly two hundred men under their command. These men also carry their own burdens of command, but as their superior, the Company Commander (and by extension, the player) also holds the power of life and death over them in turn. They represent the burden which the player must carry in keeping their men alive and well.

In his Red Sneaker series, William Bernhardt explains that the most obvious way to encourage a reader to empathise with a character is to give them a trait or two which the reader is likely to admire.

This is the first step of turning a platoon leader from a list of variables into an empathetic character. We can then use those traits as a reference point. We can build a character’s backstory by asking how he gained those traits, his likes and dislikes based on how they relate to his virtues, and then use all of those things to create a coherent way in which that character speaks, acts, and sees the world.

To make sure those personalities build the connections they are supposed to, our current writing process is heavily geared towards ensuring our characters hit the right notes. On the advice of Chris Avellone, one of our senior advisors, we’ve been asking our playtesters to record their emotional responses to major characters, and tweaking how they are written accordingly.

These personalities and virtues are reflected through their mindsets. For example, Lieutenant Thompson is defined by his idealism, This is borne out by his unwavering patriotism, his sense of duty, and his strong moral compass. Other leaders are represented in a similar way. Since mindsets (there are eight) also determine special leader abilities in tactical combat, their personalities also correlate directly to how they perform on the battlefield; yet another reason to get to know your men.

However, this isn’t the only empathy-building tool at our disposal. Good characters change and adapt (or fail to adapt) through the changing circumstances of the story. In books and films, this arc is immutable, but in Burden of Command the player takes the role of the Company Commander. Through this avatar, they interact with their platoon leaders in ways which can end up determining how they all develop as characters.

It will therefore be the player’s job to offer guidance to their subordinates. They are responsible for their subordinates’ physical well-being on the battlefield and their emotional well-being off of it. Choosing brutal but efficient solutions carries as great a cost as doing the ‘right’ thing and then having to pay for it.Through specific interactions, the player can guide their platoon leaders in a way which allows them to pick up aspects of other mindsets in addition to the one they started with. The resultant changes to the officer’s personalities and command abilities become a partial reflection of the player’s decisions in response to the stress of the war.

Emphasising the humanity of the men under the player’s command has one other, important aspect. Although the company the player controls is fictional, the battles and campaigns it goes through were very real. The flesh-and-blood men of the 3rd Battalion of the 7th Infantry Regiment suffered and bled and died in the places which Burden of Command seeks to recreate. They were not tokens on a map to their families, their friends, and those who served with them, and it would be a disservice to pretend otherwise.

In our next devblog, we’ll be discussing how we mean to convey the story of those flesh-and-blood Cottonbalers in the most respectful and historically authentic way possible.

| Follow @BurdenOfCommand |